Vive le Pigeon

I spent a sabbatical year in Lille, France, a city surrounded by what Colonel John McCrae immortalized as “Flanders Fields.” Some of the most horrific fighting that has ever taken place on Planet Earth occurred between 1914 and 1917 not far from my home base that year at Université Charles de Gaulle. In the lovely Parc de la Citadelle in the center of this ancient Flemish city is a statue honoring, of all things, the pigeon. It is not because parks are famous for pigeons that this common avian is thus memorialized. During the First World War, before the potential of radio and telephone communications were well developed, carrier pigeons were used extensively by the French to communicate vital information among their forces. The statue honors those pigeons that died in service to the nation.

I spent a sabbatical year in Lille, France, a city surrounded by what Colonel John McCrae immortalized as “Flanders Fields.” Some of the most horrific fighting that has ever taken place on Planet Earth occurred between 1914 and 1917 not far from my home base that year at Université Charles de Gaulle. In the lovely Parc de la Citadelle in the center of this ancient Flemish city is a statue honoring, of all things, the pigeon. It is not because parks are famous for pigeons that this common avian is thus memorialized. During the First World War, before the potential of radio and telephone communications were well developed, carrier pigeons were used extensively by the French to communicate vital information among their forces. The statue honors those pigeons that died in service to the nation.

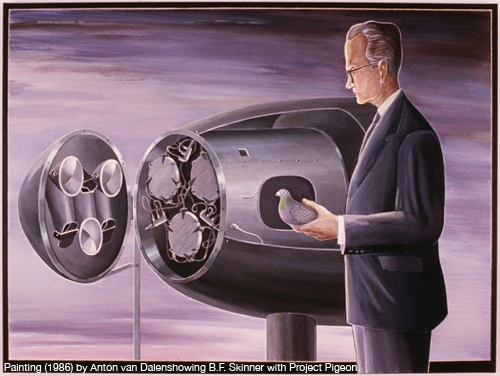

Fast forward to the dark days of the Second World War. B. F. Skinner takes a memorable train ride across the American Midwest that yielded the following recollection:

“I was looking out the window as I speculated about these possibilities, and I saw a flock of birds lifting and wheeling in formation as they flew alongside the train. Suddenly I saw them as “devices” with excellent vision and extraordinary maneuverability. Could they not guide a missile? Was the answer to the problem waiting for me in my own backyard?” (The shaping of a behaviorist, 1979, p. 241).

The possibilities about which he was speculating related to developing a reliable system by which pigeons might guide bombs to their targets. The result of his speculations was project ORCON (for "organic control"), described in detail in an article in the American Psychologist (1960, 15, pp. 28-37). He did, in fact, through the use of positive reinforcement, teach pigeons to accurately place bombs on targets. Unfortunately for the program (but perhaps fortunate for the pigeons who would make the ultimate sacrifice for their accuracy, because they were located in the head of the bomb), radar was developed at the same time and electronics won out over organic control. ORCON, however, had several huge effects on the development of a science of behavior. Skinner developed sophisticated behavioral training and maintenance techniques that previously were unheard of in the world of psychology. And the lowly pigeon thus was elevated in status to the subject of choice in behavioral research.

The possibilities about which he was speculating related to developing a reliable system by which pigeons might guide bombs to their targets. The result of his speculations was project ORCON (for "organic control"), described in detail in an article in the American Psychologist (1960, 15, pp. 28-37). He did, in fact, through the use of positive reinforcement, teach pigeons to accurately place bombs on targets. Unfortunately for the program (but perhaps fortunate for the pigeons who would make the ultimate sacrifice for their accuracy, because they were located in the head of the bomb), radar was developed at the same time and electronics won out over organic control. ORCON, however, had several huge effects on the development of a science of behavior. Skinner developed sophisticated behavioral training and maintenance techniques that previously were unheard of in the world of psychology. And the lowly pigeon thus was elevated in status to the subject of choice in behavioral research.

“But why pigeons?” I am often asked when describing my own research. They are hearty animals, with long life spans, making them ideal for long-term studies of behavior, is my first response. “Yes,” say my inquisitors, “but why don’t you study humans, who, after all, are what you are really interested in?” Because, like any basic scientist, I am interested in studying pure forms under well-controlled conditions. After all chemists don’t use make-up or deodorant as their models for basic chemical reactions, and physicists don’t use construction sites as their models for basic physical processes. All scientists start with simple preparations and then generalize to more complicated situations. Pigeons (and, for many psychologists, white rats) have provided a way of examining the basic processes from which all learning is built. Start with something simple and build it to complexity.

Nor is it the case that people like me who conduct learning research with pigeons are really all that interested in pigeons per se. All living organisms share the ability to learn. Learning in pigeons is not, of course, the same thing as learning in people. But, there are similarities, and to understand learning in the simple case contributes greatly to understanding it in all its complexity in the everyday lives of humans. Pigeon behavior is interesting, but understanding it is not the end-goal of behavioral research. Pigeon behavior is one of the means to the end of understanding human behavior, and in so doing creating the possibility of bettering the human condition, which is the end goal of much scientific activity.

Nor is it the case that people like me who conduct learning research with pigeons are really all that interested in pigeons per se. All living organisms share the ability to learn. Learning in pigeons is not, of course, the same thing as learning in people. But, there are similarities, and to understand learning in the simple case contributes greatly to understanding it in all its complexity in the everyday lives of humans. Pigeon behavior is interesting, but understanding it is not the end-goal of behavioral research. Pigeon behavior is one of the means to the end of understanding human behavior, and in so doing creating the possibility of bettering the human condition, which is the end goal of much scientific activity.